Works

Goutam Halder has showed up in 100 plus plays in front of audience and coordinated in more than 40 directions.

Qualification

Goutam Halder has succesfully completed Comprehensive Theatre Training in 1986-1987 at Nandikar (Guru Rudraprasad Sengupta). Teachers and Trainers included Sombhu Mitra (theatre legend), Khaled Chowdhury (legendary Scenographer), Tapas Sen (renowned Lighting Designer), Late B V Karanth, Prof. Jamil Ahmed (NSD, Delhi/Dhaka University, Bangladesh and University of Warwick, England), Martin Russell (Fools Theatre, New York) amongst others.

Goutam Halder is a Bachelor of Science in Zoology from Calcutta University.

Goutam Halder Sustained Training in Dance & Movement:

- Trained in KATHAK at Padatik Dance Centre, Kolkata under Guru Vijay

Sankar (1984-1985) - Trained at BHARAT NATYAM in Kerala Kalamandalam, Kolkata under Guru Govindan Kutty and Thankamani Kutty (1984-1985)

- Training in MODERN DANCE & MOVEMENT AND MARTIAL ARTS under Guru Sudipta Kundu (continuing since 2000)

- Training in Classical Vocal Music under Guru Ashis Chattopadhyay and Guru Prabir Datta (continuing since 1986)

WORK & CONTRIBUTION

01.

Leading Director & Actor of Naye Natua

Naye Natua is a theatre group originated by Indian theatre actor and director Goutam Halder.

02.

Leading Trainer in various Projects

Goutam is most successful in formulating a different style of acting of his own

03.

Activities in other theatre troupes

Goutam Halder has succesfully performed in Nandikar and many other groups

04.

Lecturer & Demonstrator

Apart form direction and acting Goutam works as Lecturer and demonstrator in various institutes

05.

Works in Films

Goutam Worked in various films including Commercial as well as docu-feature films

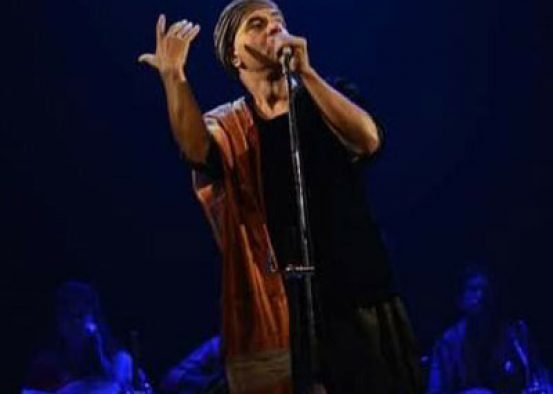

Maramiya Mon/ The Gentle Spirit

Concept and Synopsis

This latest Production of Naye Natua may claim distinction on very many counts. The production has been mounted simultaneously in Bengali, English and Hindi: Maramiya Mon and The Gentle Spirit. It is a pro-action in the wake of space-erosion Theatre is being subjected to by ‘consumeristic’ culture of the day.

This latest Production of Naye Natua may claim distinction on very many counts. The production has been mounted simultaneously in Bengali, English and Hindi: Maramiya Mon and The Gentle Spirit. It is a pro-action in the wake of space-erosion Theatre is being subjected to by ‘consumeristic’ culture of the day.

On the stage, we see and hear the lonesome inscape of an endangered soul; in the process, we experience story-telling of a different genre. Who the audience is, the launching-pad, the father confessor, the judge, the other one of this narrator, we never know. Isn’t that what a man precisely does during his search for innermost invisible and unknown still-point ! The performer here speaks, mumbles, moves and stumbles and, eventually, discovers his own style of story-telling.

In this Production, Tapas Sen responded to the words of Dostoyevsky with the artistry of a master painter; time and again, he ushered us from the external to the innards, from the informative to the experimental, from the daily to the elemental. Sanchayan Ghosh plays like a conductor with innumerable notes of colours and laeds us into a kind of an ancient cave – a frozen Symphony of colours and contours. In Swatilekha Sengupta’s music, our own classical raga Yaman blends into the structure of the Western Classical, creating an ambience of profound sadness; yet, amidst this grand music, one, again and again, hears a faint wail which begins to echo and re-echo the eternal cry of a haunted soul.

And all these have been catalysed in this production by the dedicated labour and pure sweat of Goutam Halder and Naye natua; everything has revolved round the Acting of Goutam Halder which is at once alert, ferocious, volcanic, transparently child-like and, often, holily disinterested!

All these combine to make Maramiya Mon / The Gentle Spirit a luminous addition to contemporary Bengali Theatre. Shamelessly I have to assert these because the waters around are troubled and many have flocked eagerly to fish in them. It is indeed difficult to distinguish between junk food and delicacies prepared by our Grandmas, – between thr gossip and the gospel Beware Connoisseurs ! These words of mine are just to help the Rasikas : Do try, taste and, only when satisfied, bless the new-born if it has deserved your benediction!

Rudraprasad Sengupta

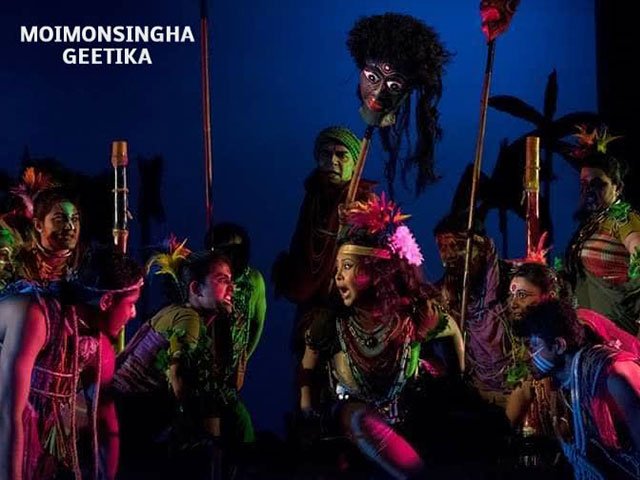

MOIMONSINGHA GEETIKA

Concept and Synopsis

The characteristics of the balladry of Moimonsinha Geetika are from a Matriarchal society. To choose husband, freedom of love, to marry in old age, all are the characteristics of a matriarchal society. Love in this society is like a divine wild flower.

The vices of city life cannot destruct this divineness. In this society selection of partner are more valued and greater than marriage. These folk literatures are like history of mankind. According to Dinesh Chandra Sen, a schedule caste Brahmin named Dwija Kanai created this ballad of Mahua (Maimansinha Gitika). The ballad starts with a beautiful secular style. To the long way in the north there is Gara Mountain. There lived a Brahmin with his six months old daughter. A leader of a gypsy group Hoomra stole (kidnapped) beautiful girl one night. At the age of sixteen this girl fell in love with a prince Nader Chand. Hoomra did not like this love affair. At the end of this folk ballad Hoomra ordered Mahua to kill Nader Chand. But Mahua kills herself instead of killing her husband. Afterwards the Gypsy Group killed Nader Chand.

In Bengals folk literature Mahua (A ballad of Moimonsinha Geetika) has been representing womanhood of our society.

Director’s Note

While reading Moimonsingha Geetika the balladry of Mohua and Nader Chand has inspired me so much. We have performed many serious political and social plays dealing with complex problems of adult existence. The ballad of Moimonsingha Geetika explores all complexities as well as the purest Love that mankind can treasure. This story speaks of ideals and norms and manners of society, the status difference and its effects on human relationships. However, the love, which inspired them nourishes all from the prince to Humra, the gypsy leader. Our sole task presenting the play is to capture the essence of that heart pulsating at the core of these tales. The performance style of this theatre is the traditional story telling pattern incorporated with popular western forms of movements along with folk tunes and all these fused into an organic whole which will explore the poetry in essence, spirit and soul.

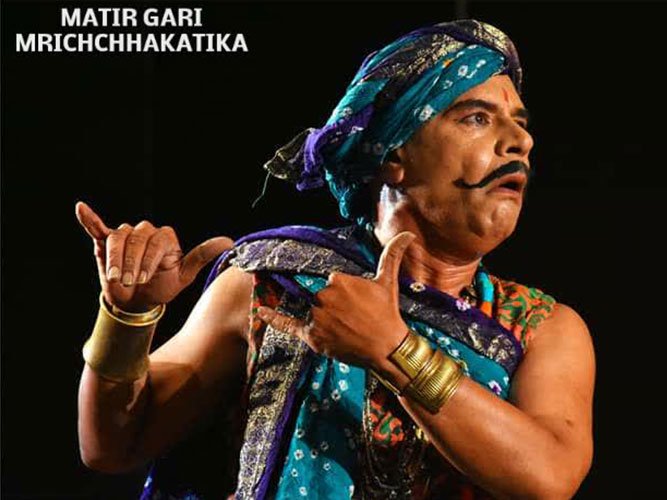

Matir Gari Mrichchhakatika

Concept and Synopsis

This play attracts me not only for  its classical fervor but for its greater social and political scenario and its portrayal of a gallery of varied people ranging from kings to gamblers, courtesans, thieves and so on. The goodness of the characters does not come out from their social conditioning but from inner virtues and truthfulness. Aesthetically this play is a brilliant example of theatrically vibrant images, metaphors and conjures. The dramatic actions of this play has also varied turns and movements comprising the inner conflict of different interests and the easy swaying of many artistically enriched emotional and aesthetic impressions.

its classical fervor but for its greater social and political scenario and its portrayal of a gallery of varied people ranging from kings to gamblers, courtesans, thieves and so on. The goodness of the characters does not come out from their social conditioning but from inner virtues and truthfulness. Aesthetically this play is a brilliant example of theatrically vibrant images, metaphors and conjures. The dramatic actions of this play has also varied turns and movements comprising the inner conflict of different interests and the easy swaying of many artistically enriched emotional and aesthetic impressions.

The play is multilingual and hence portraying multi cultural aspects. Thus, this play reflects the greater world both mundane and royal. The realization of greater and lesser souls, their inherent values, principles and ideas are beautifully woven in this classical play. The evaluation of both the world within and without in such a unique and earthly way is rare to be found in our classical age of theatre.

Director’s Note

Mrichchhakatika portrays in a metaphorical way the essential conflict of social beings torn between good and evil. On one hand there are the king Palaka and his brother in law, Shakara – rich, mighty and rogue. On the other hand, there is a trail of and poor persons like Charudatta, Sharbilak, Sambahak, Durdurak, Sthabarak, Bardhamanak, Madanika, Radanika, Goha, Ahinta. But there is only one exceptional character – Basantasena, the protagonist. She is rich but characteristically truthful. Her inherent honesty indulges her to forsake all her treasures and ornaments and embrace the destitute Charudatta.

In this play the clay cart plays most symbolic role, so, when it appears on the stage, laden with gold ornaments, the very inanimate cart becomes the ideogram of honest and candid animated beings – an incarnation of the principal theme of the play.

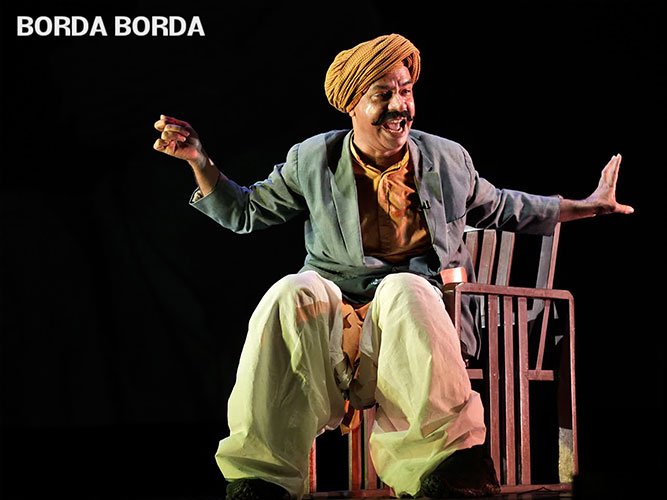

BORDA BORDA

Synopsis

It is a story of two brothers. The younger one is truant, and the elder is an all-work Jack. One is nine, and the other, fourteen. Yet it is the younger that comes first in the exams on every term, and the older repeats the story of his failure. The younger brother, now an aged man, recounts his childhood days in an interview before a camera. As we listen to the interview and watch it at the same time, the image of the ridiculous man in the elder brother fades into the larger–than–life image of a man who brings before us the essence of family ties, social bonding, education, and the values inherited. We listen, feel, and learn on the stage and across; so does, as it seem, the author himself having his story retold from letter to dramatics.

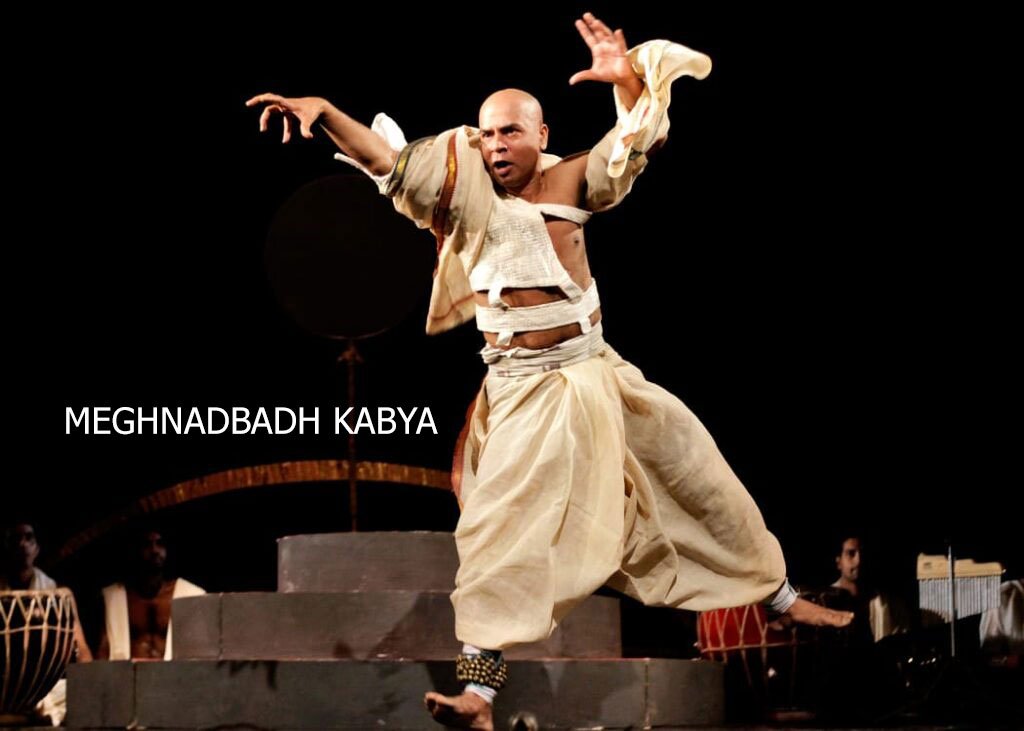

It is a story of two brothers. The younger one is truant, and the elder is an all-work Jack. One is nine, and the other, fourteen. Yet it is the younger that comes first in the exams on every term, and the older repeats the story of his failure. The younger brother, now an aged man, recounts his childhood days in an interview before a camera. As we listen to the interview and watch it at the same time, the image of the ridiculous man in the elder brother fades into the larger–than–life image of a man who brings before us the essence of family ties, social bonding, education, and the values inherited. We listen, feel, and learn on the stage and across; so does, as it seem, the author himself having his story retold from letter to dramatics.MEGHNADBADH KABYA by Michael Madhusudan Dutta

The play opens with an invocation of the Muses, Devi Saraswati in particular to inspire the narrator with an inward surging that could make him sing a song of a lofty theme describing the fall of a mighty hero.

The narrator, Kathak, leads us to Lanka, to the court of Ravana who laments the death of Birbahu, his son, who took charge of the battle and lost it, with his life, after a valiant struggle. Wh8ile facing a position to answer for the loss of so many worthy war-heroes that is caused by the king’s abduction of Seeta, Ravana defends it with the zeal of an indomitable Kshatriya who would rather stake everything to fight as enemy than to probe a cause. Instead of looking for the next general he decides to go to himself to lead the war. But Meghnad, most valiant of his sons arrives, intervenes, and offers his service. Ravana after some hesitation gives his consent and orders the ritual for his ablution, the act of “Abhisheka”.

The narrator, Kathak, leads us to Lanka, to the court of Ravana who laments the death of Birbahu, his son, who took charge of the battle and lost it, with his life, after a valiant struggle. Wh8ile facing a position to answer for the loss of so many worthy war-heroes that is caused by the king’s abduction of Seeta, Ravana defends it with the zeal of an indomitable Kshatriya who would rather stake everything to fight as enemy than to probe a cause. Instead of looking for the next general he decides to go to himself to lead the war. But Meghnad, most valiant of his sons arrives, intervenes, and offers his service. Ravana after some hesitation gives his consent and orders the ritual for his ablution, the act of “Abhisheka”.

The narrator then takes us to the celestial abode of Lord Indra, the God of the Gods. We find him shaken with fear for Meghnad who once made him accept a most humiliating defeat in direct confrontation. Indra devises to court the favour of Lord Shiva through Devi Uma( Durga) and win from him the Power Ammunition to kill Meghnad. Pleased with Indra and Rama’s devotion Uma sets forth to tempt Lord Shiva to an act of wild love-making and thus elicit from Him a device for the slaying of Meghnad. Lord Shiva, even though seeing through the design, could not help to be enamoured by the charm of Parvati. On his advice, Indra is sent to Maya, the Dark Goddess of Magic and illusion, who gives the Weapons that, would see an end of Meghnad. The act of winning of Ammunition or “Astralabha” ends here.

With the narrator we now come to the Pleasure-garden of Prince Meghnad where Pramila, the waiting for her husband. On getting the news of siege of Lanka and his army, Pramila, with the force of her warlike Amazons, sets forth to free Lanka and the Prince from the enemy’s clutch. But before the majestic female troupe, resplendent with the glory of the heavenly powers,

Rama reverently makes way for the army to enter the city of Lanka. Pramila meets Meghnad, and the lovers were rejoicing their union, prepare and brace themselves for the fateful vigour and prepares for a battle that would be decisive. Hence ends the act of Meeting of the lovers or “Samagama”.

The narrator now comes to the act of ‘Preparation for the battle’ or “Udyog”. In both of the camps, of Rama and Ravana the Preparation is showed with great detail. Helped by Maya, Lakshmana, brother of Rama goes deep in the heart of the forest and offers his devotion to the War-goddess and asks for her blessings. It is granted to him, on the way, he meets Lord Shiva, protector of Lankan Dynasty, who also gives way to him. Heaven and earth join hands to wreck Meghnad. Unaware of all these fateful design Meghnad takes leave of his beloved wife and Parents and sets out for the battle. Only a shadow of an omen flickers in the heart of the Sati, the chaste Pramila, who perceives this could be their last meeting on this earth.

The fifth act, the slaying of the Hero or “Badh” begins with Lakshmana and Bivishana, the traitor- brother of Ravana; Bivishana leads Lakshmana through the secret passage to the Nikumbhila temple where Meghnad, after offering his prayer, would attain invincibility, while unarmed and busied with the rituals, Meghnad is confronted by the duo and challenged to a war. Meghnad asks their leave to collect his weapons according to the charter of the war regulations. But Lakshmana, declines and empowered by Maya, kills him in an unjust fight. Bivishana also feels a pang of conscience over the fall of the mighty hero and laments his own plight as a traitor.

The eight and the last act, the narrator leads us to the scene of cremation where the pyre is lit for Meghnad. Pramila also climbs the fiery bed where her husband is lying. An armistice is declared by Rama for the funeral. The whole city of Lanka mourns the death of Meghnad, the last of the Mohicans

Director’s note

We had a regular practice of working with poem in our theatre training classess. An influence of the vvenerable elders of theatre, no doubt.

I once shought advice from one of my friends on what text should we work if we are to improve our ability in pronunciation. As, it happened, my learned friend , a professor of bengali literature, instantly came out with an ready recitation of an extract from Meghnad badh Kabya. I was started—-my ears drank the music it poured. Ignorant as I was, I asked him what text he was reciting from .

I begin to work with Meghnadbadh from the very next morning. We had an extract from this great poem as a text when we are in school, but I could not imagine then what wealth it had in store for me. Now, on the very first day, the poem speeded into the inmost layer of my being : its colour, rhythm, and magic flashed before us the plight of a great person, a lone’s crusader who was traped in a snare of love’s labour, of allurement, of ambition and hope, of frustration and dejection; yet who, refusing to be conquered rose above it by singing a heavenly song that was born in the gutter of poverty but looked at the stars of immortality. It enchanted us, inspired us as we set ourselves to the Herculean task of matching our tunes to the poet’s.

I did not even dream then to bring an epic of this stature to the stage. But li! Hardly a couple of days passed before we could find, to our great amazement, we were already acting the lines rather than just reciting them.

The rest———no, not silence, but what you might find us doing on the stage!

Thakurmar Jhuli

The play comprises two stories; in each, the protagonist is a young lady. The play begins with ‘Kiranmala’, in which feature Arun and Barun, two brothers, and their sister, Kiranmala- all of them offspring of the king. Immediately after they were born, they were thrown into a river by their wicked maternal aunts. They were rescued and brought up by a kind-hearted Brahmin. The story narrates how later, by dint of sheer courage, grit and resourcefulness, they were reunited with their parents, and their rights restored.

The second story is that of Kanchanmala, the queen, and her maid Kakanmala. As against this pair, there is another: a prince and his friend, a cowherd. The prince got married and was enthroned. On being king, he turned his back on his best friend, the cowherd, snapping all ties. And for that sin he fell victim to an incurable disease. Kakanmala too, wily and wicked, insinuated herself into the queen’s confidence, claiming that she could cure the king. Trustful, the queen engaged her as maid. By trickery she fooled the queen, the other members of the family and the king too to usurp the rightful queen. Finally, with the help of the cowherd friend, the real queen got out of the mess to re-establish her rights. The king and the cowherd too were estranged no more.

Director’s note

When as a child I first hung on my grandmother’s lips listening to the tender tales of Thakurmar Jhuli, as in the case of other children, an onrush of love, affection and wonderment took entire possession of one.

As I grew up, I now and then thought that maybe I had now outgrown that childhood state of enchantment. But, no, at times welling up from deep within, the half forgotten memories of the past would carry me to the realm of wayward thoughts. But why? Wherein lies the real strength of these simple tales? It is from the search that the idea of making a play based on two or three stories from Thakurmar Jhuli has eventually emerged.

We have performed many serious political and social plays dealing with complex problems of adult existence. Now, let us for once get back to our own treasure trove to freshen our heart and soul. Do the tales of Thakurmar Jhuli too not contain insights into what is missing in our society and in the way we do politics and how we may live a better life? Then, of course, the insights are spelt out in a language, which speaks only to our subconscious selves. The fairy tales are not those of Europe, admittedly. They speak of ideals and norms and manners of faraway places. However, the love, which inspired them nourishes all from the little prince to the prattling peasant boy, for they are all fed by the deep affection of the Bengali mother. Our sole task presenting the play is to capture the essence of that heart pulsating at the core of these tales.

Catchline:

“What else there in our country is the indigenous stuff as precious as Thakurmar Jhuli?”

Rabindranath Tagore